Between May and December 2015, PBI Mexico will publish a series of interviews with Human Rights Defenders which we accompany or with whom we maintain a close relationship. This month we present an interview with Silvia Mendez, member of the Paso del Norte Human Rights Center, from Ciudad Juarez.

Due to the situation of risk faced by the staff of the Paso del Norte Human Rights Center and to the relevance of their work, PBI started the accompanying the center in September 2013. The center was the first organization to be accompanied by the PBI team in North Mexico.

Silvia Mendez, a woman human rights defender

My name is Silvia Méndez. I have worked in the Human Rights Center, Paso del Norte, in Ciudad Juarez since 2003. Our task is to defend the human rights in the city, to work for justice and truth. This work is my life. There is nothing more rewarding than to do what you like doing. This helps me to go ahead.

In the early years doing this work I did not know that I was a human rights defender, but now I think I've always been one. At different times in life you react to things that seem unfair to you, such as the situations that indigenous women face, and you say, “I have to do something”. I felt moved by the disappearances of women. The ladies of the community I worked with told me that one night they heard a girl scream who had been taken away in a car. I asked, “What did you do?” They said, “What could we do? what could we do Miss ?” I had a feeling of helplessness. How was it possible that these things were happening and we could not do anything?

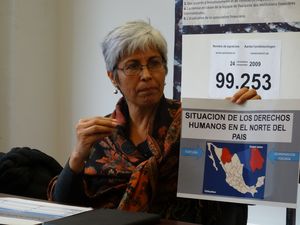

Photo: Silvia in a meeting with political representativies during her advocacy tour through Europe © PBI Mexico

I decided to start working for this Human Rights Center on October 6th, 2004, when the body of a Central American woman was found some steps away from my house. It is possible that this woman came with a group of undocumented immigrants. Her family may have never known where she was and what had happened to her. So I said to myself, “You can do something”.

As a woman this work is not easy. No, it's not easy. You have to state your position and you have to argue. I think for a woman it is three times more difficult than for a man to make her voice be heard. In my work as a woman’s rights defender I must be firmer, clearer, harder. This is what I have experienced in different contexts. I have to be more direct, more persistent and more insistent.

The human rights center is a space that is growing every day and where we are improving our expertise. We came here accidentally, with the best of intentions but as new comers. And with the experience we gain and the training we are receiving we are growing and improving our work as individuals and as a team.

The Human Rights Center Paso del Norte and human rights violations in Ciudad Juárez

In our country we have a serious problem. There is no education that trains people to become citizens. That is the challenge; how to tell the new generations that we must participate as citizens in the groups in which we are part of, in the civil society organizations and in the social movements. It should be clear for everyone that we are always a part within a society.

I am encouraged by knowing that I am a citizen and that I participate in this space built along with other colleagues with the same longing and with the same dream that we can do something. We rose from nothing. We had no resources, no experience, we had nothing, but we had clarity on what we wanted. We wanted a more just world and therefore we have worked. I think that we are leaving this idea to the next generations; that it can be done. It is possible to create, to develop dreams and to make them become true.

The Human Rights Centre Paso del Norte works with the inhabitants of the districts of Ciudad Juárez. Until the outbreak of violence we were offering trainings on human rights. The people in the neighborhoods were trained by us and also by organizations like the Agustín Pro Juárez. They gave them training on economic, social, cultural and environmental rights. Mostly the people that came to the trainings were women. They entered a process of making the defense of human rights their own and started committees in their colonies. They were very concerned about environmental issues, water issues, and train tracks crossing their neighborhoods without child safety measures. A team of human rights educators was formed. Yes, there were results. I saw the work of the promoters. They had a clear understanding of human rights. That worked a few years. Unfortunately later the violence came into the region, and there was no possible way to continue this community work. Nobody could leave home and join a meeting in the evening. The security conditions for doing such things did not exist.

Since 2007 we lived in a situation of great violence. The circumstances in the life of Juárez have always been violent but the situation got much worse. In those years we lived in chaos. There was confusion. Many executed people started to appear in the city. The government said that the organized drug gangs were fighting the territory and sent the army. But the community never knew clearly who was who. There were armed groups and people did not know if they were drug traffickers or agents from the government.

In the Human Rights Center we started to work in cases of torture and forced disappearance and we started to be victims of threats and direct attacks. It was hard to decide where to turn or how to address the issues. We learned how to deal with these issues alongside the same people who brought us the cases. For example, for the cases of kidnappings we recommended the families to lead the negotiations directly themselves.

The current risks faced by the team of Human Rights Centre Paso del Norte

I realize the risk I face, especially sometimes, such as when I accompany victims who are being threatened. I gave a ride, for example, to a woman who had been kidnapped. It was night and I took her to a certain place. I did not think at that time that she was at risk. I just thought I had to take her with her children. I did not become aware of the risk until they left and I found myself alone in that part of the city at night.

The rooms where we are working have been raided. When they came to our offices we all felt vulnerable. They could find personal information. We are always careful with our social networks and our families, who usually do not come to the human rights center, but are a part of us. We must anticipate the risks.

And I've lived the risks more indirectly, supporting teammates, such as the legal team and their families, when they have been victims of aggressions. Some relatives who were testifying at hearings have been persecuted by police agents. At these times I worry and get tense. But I also think, and I always think, fear does not paralyze me. I see what I can do, and that helps me. It's the same with the team. When there is a risk or when the lawyer called us and told me there were police members outside of my house or there are trucks waiting out there, what can we do? Then we react, we analyze and make a strategy to measure the level of risk, we think about how to protect our colleagues, with whom we can meet and where to seek support.

Something that makes the majority of us vulnerable is that we are living in outlying areas of the city where the risk is high. For us, these places are not as dangerous because we live there but still that make us very vulnerable. If someone wants to follow us, we can be easily located in our homes and there are houses without even a minimum level of security. Some colleagues travel on foot to come to work and that worries me a lot. I luckily have a car and move with it, but there are colleagues who travel by bus or on foot. In our center I think the most vulnerable are the lawyers or the director of the center because they are the ones who are the most visible.

Photo: Members of Paso del Norte HRC during an advocacy workshop facilitated by PBI, Ciudad Juarez © PBI Mexico

The Figueroa case, an example of harassment for fighting against arbitrary detention and torture

We have successfully supported the so called Figueroa case. Due to this case, we have registered continued attacks against the lawyer and the relatives of the detainees. Four young men were arrested, and three of them belonged to the same family. They are three brothers who were arrested arbitrarily with a friend, all accused of being part of an extortionists gang, and one of them was a child under 14 years.

When they were detained and accused of the crimes of kidnapping and blackmailing, they were asked to incriminate other young people studying with them and to incriminate themselves. They were given papers with what they had to say and were tortured until they did so. They described to us their detention and the tortures they were victims of.

In this case, each time that there was an audience or something important happened in the process, their relatives were harassed, and there was presence of police forces at the homes of the relatives. They saw armed people that looked around outside the house, or the neighbors commented that they saw trucks such as those used by the justice police outside the house making videos of the relatives’ houses. This created fear and the family decided to leave the house and to go to another place in the town. The wife of one of the youths arrested was chased by a van like the ones used by the justice agents. She is an American citizen so she could cross to the other side of the border.

During several days, a van that is used by the police corps, circled the house of one of our partners, a lawyer, while she was at a hearing of this Figueroa case. They inspected the house all around, both the front and back yard. The husband was very concerned because he and our partner, the lawyer, have a baby. We decided they had to leave their home and be out for three months as a safety measure.

I calmly tell you this right now, but it's hard to describe what happens to us at the time. We really get tense and we start thinking about what can happen to us. But from these feelings we try to go further and see what we can do.

To be heard: The need of national and international support for coping with the aggression

We have learned with Peace Brigades International and with other international organizations and we have learned through our experiences. The experience we had at the time the office was raided showed us the importance of international reactions, because the aggressions were halted. And to get that international reaction our voices needed to be heard and with it our version of the facts that were happening in our city. Elsewhere we need people to have a wider understanding of the situation in Ciudad Juárez and in Mexico, because usually there is another, more positive, view of what happens in this country and in our city.

In Mexico we are part of the National Network All Rights for All, a network of Mexican human rights organizations. When we suffer attacks, we have had their support. I appreciate this support very much because they immediately react and tell us to not worry about the financial issue and that if we need to relocate someone they take care of that part.

Since 2013, a State Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders at Risk has existed in Mexico. We presented the case of the lawyer harassed during the Figueroa case to this office, but the reaction was not very warm. We were told that the risk level was middle while for us, what we were experiencing was very serious. Considering the level of violence in the city and the possibility that something could happen to the lawyer, her family or child, we felt responsible for their safety, which was the most important thing to us. This mechanism, the authority, did not see it the same way.

The process was very disappointing, because they proposed protective measures for the lawyer such as a change of address, which we had already done. They wanted to bring our colleague to live in a “safe house”, controlled by the police. It was a place where our colleague was surely not wanting to go. I said to the security expert who they sent, that the lawyer had not been consulted about where in the city she would want to be or where she would feel safe. We asked for four mobile phones for the four areas of work we have in the team and for a circuit of cameras for the offices. We were offered a single phone and a camera, but then where were we going to put it? We could put it in front or on the back side of the building.

No, we did not see a willingness to respond to our security problems because the results spoke for themselves.

* This interview was conducted by Susana Nistal and translated by Annie Hintz