Not every family can celebrate Mother's Day in the same way. In Mexico, thousands of mothers spend the 10th of May like any other day: searching for their loved ones and demanding authorities to investigate the disappearances. This Sunday, like last year, volunteers of Peace Brigades International (PBI) will accompany the "March for Dignity" in Mexico City. Regarding the occasion PBI published this analysis.

Mothers and activists during the demonstration of 2014 © PBI Mexico

"The night has lengthened, the agony has lengthened, and we continue as always, slip-sliding, while the Mexican government continues to find nothing": parent of one of the 43 students who were forcibly disappeared on 26 September, 2014 in Iguala, Guerrero."

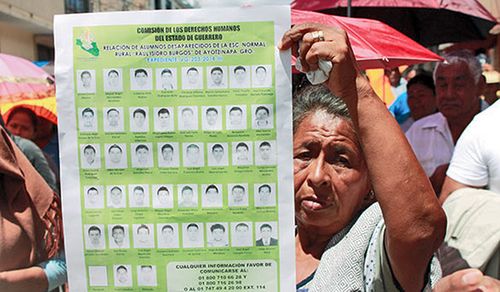

The disappearance of the 43 students of the Raúl Isidro Burgos teacher-training college in Ayotzinapa has catapulted Mexico into the spotlight of the international community. Since then, all over the world, activists and protestors have adopted the slogan “#Fue el Estado” (It Was The State) as the slogan in a global campaign demanding that the institutions involved in the events at Iguala be held responsible for their actions. In this context, shows of solidarity with the families of the students and repudiation of the actions of the authorities have multiplied. The case of the 43 students is being handled by the Tlachinollan Centre for Human Rights which has been accompanied by PBI since 2003.

Despite the importance of the case and the pressure on the Mexican authorities to submit viable results of investigations, uncertainty persists. Of the several versions about what happened the night of 26 September, the version of the Attorney General's Office (PGR), which confirms that it was the mayor of Iguala, Jose Luis Abarca, who ordered the attack, and the version of Omar Garcia, a student who survived the attack and who puts elements of the army in the scene of the crime, which stand out.

Due to the lack of certainty surrounding the conclusions presented by the PGR, relatives of the disappeared asked the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) to accompany the case. In February 2015, the EAAF published a report which revealed seven procedural errors in the PGR´s investigation.

In November the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), in an agreement with the Mexican government and the representatives of the 43, assigned an Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (IGIE) to, amongst other things, elaborate a plan to search for the disappeared, alive, and to carry out a technical investigation to determine criminal liability. This group published reports during its first visit to Mexico in March as well as after the second, in April. Amongst other requests, the IGIE has solicited that the homicides be reclassified as enforced disappearance and that new lines of research be opened.

Mexican civil society organisations and the families themselves are also working so that the case cannot be forgotten. As a result, Ayotzinapa has awakened the Mexican population, which took to the streets across the country to demand the presentation, alive, of the 43. Civil society organisations report that many of the events that followed were marred by acts of repression and criminalisation of protest with several cases of police abuse and arbitrary detentions.

Relatives of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa © PBI Mexico

“The information received by the committee shows a context of generalised disappearances in a great part of the country, many of which could qualify as enforced disappearances” United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances

But Ayotzinapa is neither an exceptional nor an isolated case, a fact which was thrown into sharp relief by the search operations for the 43 students. The PGR has indicated that between that and February 2015 38 mass graves were found in Iguala, containing a total of 87 bodies – none of which could be associated with the attacks of 26 September. The question being asked in Mexico is, who do these bodies belong to? According to latest figures from the PGR, there are at least 22,322 possibilities. This is the number which the PGR accepts are "missing" in Mexico. A frightening figure, but one which does not fully reflect the reality of disappearances in the country. According to United Forces for Our Disappeared in Mexico (FUNDEM), this figure rises to 17 a day when cases which go unreported due to fear or lack of faith in the system are taken into account.

In 2013, Human Rights Watch documented 250 cases of disappearances, 149 of which could be classified as enforced. In 60 cases, HRW could show direct collaboration with organised crime and, in 20 cases of enforced disappearance carried out by the Navy during June and July 2011, the size of the operation suggested a significant level of planning and coordination.

The issue is not new either: the root of the problem of enforced disappearances in Mexico dates back to the sixties and the so-called Dirty War. According to Amnesty International, at least 700 cases of enforced disappearance remain unsolved from the period. One of these cases is the case of Tita Radilla´s father, Rosendo Radilla. Tita Radilla has been accompanied by PBI since 2003, due to the level of risk she incurs with her untiring search. Rosendo Radilla was disappeared after being detained at a military checkpoint in Atoyac de Alvarez, Guerrero, in August 1974. In 2009, the IACHR established the responsibility of the Mexican State for the violation of the rights to freedom, personal integrity and life of Mr. Radilla. Because of the significance of the failing, and insofar as it imposes restrictions on military justice, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) filed the case in the world memory programme.

A report published by the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances highlights that the Mexican state recognised the responsibility of three presidents in the atrocities of the Dirty War, thus putting paid to the theory that members of the armed forces acted on their own initiative. Unlike the Dirty War atrocities, which occurred in a context of repression of political opposition, today it is difficult to identify a pattern that connects the victims of enforced disappearance.

Tita Radilla and members of AFADEM, Guerrero © PBI Mexico

However, there are organisations who point to the level of collusion between organised crime and the state as a key element in understanding the problem. There are other organisations who understand the plague as a policy of terror, particularly in regions rich in natural resources such as water, minerals and gas which offer an extraordinary profit for the extractive industry. The Sierra Tarahumara of Chihuahua is a region rich in precisely these resources and indigenous peoples there have faced various conflicts due to extractive processes. Simultaneously, the number of disappearances, especially of young men, has been multiplying. The Centre for Human Rights of the Woman (CEDEHM) has documented over 1500 cases of disappearances in the northern state. In the city of Cuauhtémoc, the gateway to the Sierra Tarahumara, more than 350 people have been reported disappeared.

“Here, too, it was the state.” Families of the disappeared in Allende, Coahuila

Undoubtedly, the phenomenon of enforced disappearances manifests itself from the north to the south of the country. In this respect, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED) stressed that the problem was "widespread in much of the territory" and that almost complete impunity was evidenced by “the almost total inexistence of sentencing”.

3 March 2015 marked four years of impunity in the case of the massacre of Allende, in the northern state of Coahuila, during which it is alleged that more than 300 people disappeared. According to eye-witness testimonies, that afternoon approximately 40 trucks with armed men arrived, blocked the exits to the town and took dozens of families from their homes in a siege that lasted days. The criminals also allegedly had the support of the municipal police.

According to the Attorney General of the State of Coahuila (PGJE), the events occurred on 3 March 2011, however no search took place until 27 January 2014, almost three years later. That same day twenty former state officials, including former mayors and police chiefs were summonsed with respect to the disappearances. In December of that year, the PGJE claimed that the real number of disappeared was 28, not 300 as reported. The families continue to seek justice.

“The Working Group recommends that the safety of human rights defenders be guaranteed, including of those who work against enforced disappearance and defending the rights of victims” Report of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances

Human rights defenders who work on cases of disappearance, particularly enforced disappearance, face a worrying level of risk, as they denounce crimes committed by the armed forces. A recent example is that of the Centre of Human Rights of the Mountain Tlachinollan, in the southern state of Guerrero, which was recently subject to defamation and surveilance by Mexican authorities.

In Chihuahua, PBI accompanies the Human Rights Centre Paso del Norte (CDHPDN) of Ciudad Juarez, which is handling several cases of enforced disappearances. Because of their high level of risk the staff of the centre are beneficiaries of various protective measures, from both the Mexican Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists and the IACHR. They have been the target of threats and harassment by federal and state authorities and have also suffered a raid on their offices, perpetrated by agents of the Federal Preventive Police, who forced the locks and smashed windows in order to enter and steal documents.

In the state of Coahuila, since February 2014, PBI has accompanied three organisations working on the issue. The Human Rights Centre Fray Juan de Larios (CDHFJL) of Saltillo and the Centre for Human Rights Juan Gerardi (CDHJG) of Torreón accompany hundreds of cases of disappearances in Coahuila and in other states, as well as accompanying United Forces for Our Disappeared in Coahuila (FUUNDEC) and Mexico (FUUNDEM). In 2007, a member of the CDHFJL was attacked while unknown men entered the centre and examined sensitive information. In 2012, the CDHJG was raided by the army, along with members of the state and federal police. The Saltillo Migrante Shelter (CMS), which documents cases of disappeared migrants, suffered 74 incidents between 2010 and 2014. For their part, FUUNDEC-M which is made up of the relatives of missing persons, have also suffered intimidation and harassment during the search for their loved ones.

The recommendations made by the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID) to the Mexican state in December 2011 are still very relative: “the safety of human rights defenders should be guaranteed, including of those who work against enforced disappearance and defending the rights of victims”.

"We're demanding that they stop searching in mass graves, that they stop searching in landfills, because we are sure that they are alive.": Parent of one of the 43 missing students

In February 2015, the UN Committee against Enforced Disappearances (CED) examined the report presented by Mexico and then published its observations on the matter. In that document, the CED highlighted that the problem was “ generalised in a great part of the country” and that impunity was “expressed by the almost total inexistence of sentencing”. When the Secretary for Foreign Affairs, José Antonio Meade, announced that there were "inaccuracies" in the response of the CED to the report provided by Mexico, PBI Mexico, along with the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT) and the International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), released a communication declaring that the findings should constitute a roadmap for Mexican authorities.

Amongst the various recommendations of the CED came the recommendations to adopt a general law on disappearances throughout Mexico, to create a single national register of missing persons and to begin investigations immediately after the occurrence of a disappearance. In fact, in 2011, the WGEID had made similar observations: a national search program with a protocol for immediate action, the adoption of a new law, and the creation of a database at a national level.

Meanwhile, between December 2014 and March 2015, different proposals for a comprehensive law to prevent and punish forced disappearances were presented. On 30 April, the Chamber of Deputies unanimously approved a constitutional reform that allows the legislature to pass laws on enforced disappearance and torture. This is a first step towards creating a General Law on Disappearances and to thus comply with the recommendation of the UN.

PBI volunteers observe the demonstration of 2014 © PBI Mexico

PBI supports the demands of FUUNDEC-M, namely that the state recognise the dimension of the problem and that it prioritise the systematisation of reports of disappearances at the national level. PBI urges the Mexican authorities to continue cooperation with the CED in virtue of Article 29 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons Against Enforced Disappearance. PBI further urges that authorities follow up on the recommendations in line with Mexico´s international commitments upon ratification of the Convention and that they accept the advice of the committee of experts who supervise its application in line with Article 26 (1).

Finally, PBI exhorts the Mexican state to publicly recognise the work carried out by human rights defenders who work against disappearance and the impunity which accompanies them. PBI considers that only by doing so can the safety of those who dedicate their lives to changing this panorama be guaranteed.